Create Your Own AI Girlfriend 😈

Chat with AI Luvr's today or make your own! Receive images, audio messages, and much more! 🔥

4.5 stars

Every unforgettable story, from a blockbuster film to a captivating fanfiction, is built upon a solid framework. This invisible architecture is what transforms a simple idea into an emotionally resonant experience that hooks an audience and refuses to let go. But mastering this craft isn't just for seasoned authors; it’s a critical skill for anyone looking to create compelling content, whether you're writing your next novel, designing an interactive AI character, or developing an immersive roleplay scenario.

This guide moves beyond dry theory to provide a deep dive into powerful narrative structure examples. We won’t just tell you what they are; we will dissect how they function using iconic stories you know and love. You'll gain access to strategic analysis and actionable takeaways that you can apply immediately to your own creative projects.

By exploring the blueprints behind the world's most effective stories, you'll learn to control pacing, build suspense, and create powerful character arcs. Prepare to unlock the secrets of storytelling and transform your blank page into a captivating world. We'll explore seven distinct structures, including:

- Three-Act Structure

- The Hero's Journey

- Five-Act Structure (Freytag's Pyramid)

- In Medias Res

- Circular Narrative

- Non-Linear Structure

- Frame Narrative

1. Three-Act Structure

The three-act structure is arguably the most recognizable and enduring narrative framework in storytelling. Tracing its roots back to Aristotle's Poetics, this model provides a clear and satisfying arc by dividing a story into three distinct parts: the Setup (Act I), the Confrontation (Act II), and the Resolution (Act III). It's a cornerstone of Western narrative and one of the most powerful narrative structure examples for creating a cohesive plot.

This structure’s enduring popularity stems from its ability to manage audience expectations while building momentum. It provides a reliable blueprint for escalating conflict, developing characters, and delivering a powerful emotional payoff.

How It Works: A Strategic Breakdown

The three-act structure is defined by key transitional plot points that move the story from one act to the next.

- Act I: The Setup. This act introduces the protagonist, their world, and the initial conflict. It establishes the story's stakes and ends with the inciting incident, an event that disrupts the protagonist's ordinary life and forces them into the central conflict. For example, in Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, this is Hagrid's arrival with the Hogwarts letter.

- Act II: The Confrontation. As the longest act, this is where the protagonist actively pursues their goal, facing escalating obstacles and antagonists. This section tests their resolve, forcing growth and change. It often contains a midpoint, a major plot twist or revelation that raises the stakes significantly.

- Act III: The Resolution. This final act features the story's climax, the ultimate confrontation where the central conflict is resolved. Following the climax is the denouement, or falling action, which ties up loose ends and shows the protagonist in their new reality.

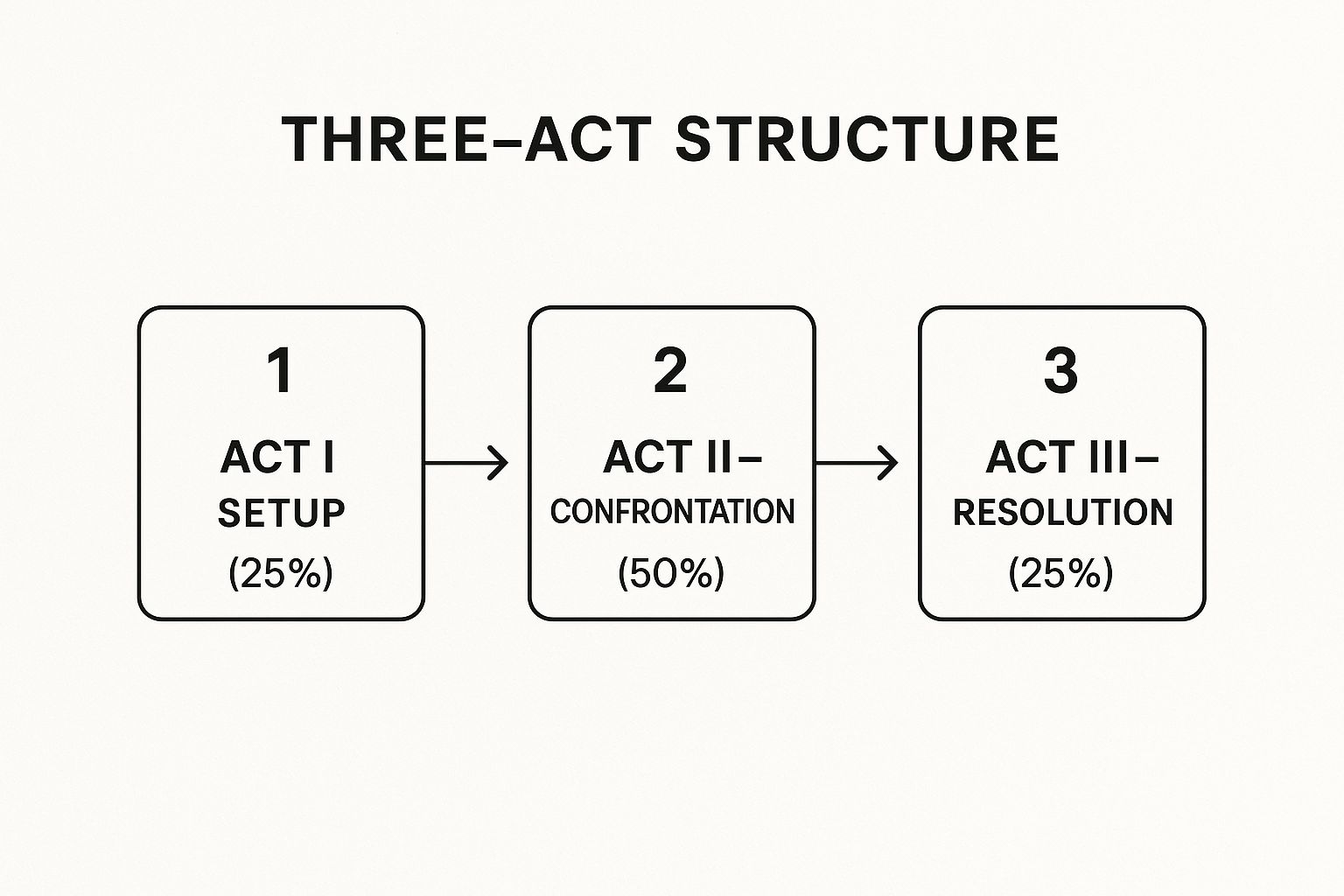

The following infographic illustrates the proportional flow of this classic structure, showing how the central conflict dominates the narrative timeline.

The visualization highlights how Act II, the Confrontation, comprises half the story, dedicating the most time to character struggle and development.

When to Use This Structure

The three-act structure is exceptionally versatile, making it ideal for character-driven stories where transformation is key. It excels in genres like action (Die Hard), fantasy (The Lion King), and adventure (Star Wars: A New Hope). Use it when you need a strong, clear plot that builds tension systematically and delivers a satisfying conclusion. It is the go-to framework for screenplays and novels aiming for broad commercial appeal due to its familiar and emotionally resonant rhythm.

2. Hero's Journey (Monomyth)

The Hero's Journey, or Monomyth, is a powerful narrative template identified by scholar Joseph Campbell. It outlines an archetypal adventure where a hero leaves their ordinary world, ventures into an unknown realm of trials and transformation, and ultimately returns home with newfound wisdom or a special boon. This framework is one of the most resonant narrative structure examples because it mirrors our own psychological journeys of growth and self-discovery.

Its strength lies in its deep connection to universal myths and human experiences. By following this pattern, a story can tap into a primal sense of adventure, struggle, and rebirth that feels both epic and intensely personal. It’s a roadmap for profound character transformation.

How It Works: A Strategic Breakdown

While Campbell detailed 17 stages, a simplified version popularized by Christopher Vogler is often used. The journey is broadly split into three phases: Departure, Initiation, and Return.

- Act I: The Departure. This section begins in the Ordinary World and includes the Call to Adventure, which the hero often initially refuses. A Mentor figure then appears to guide them, and the hero finally commits by Crossing the Threshold into the special world. In The Lord of the Rings, this is Frodo accepting the quest to destroy the One Ring and leaving the Shire.

- Act II: The Initiation. Here, the hero faces Tests, Allies, and Enemies, learning the rules of the new world. They approach the inmost cave, a place of great danger where they face an Ordeal and seize a Reward. Luke Skywalker's journey in Star Wars: A New Hope from the Mos Eisley Cantina to the Death Star trench run perfectly encapsulates this phase of trial and growth.

- Act III: The Return. The hero embarks on The Road Back to their ordinary world, often pursued by vengeful forces. They face a final Resurrection test, a climax where they must use everything they’ve learned. Finally, they Return with the Elixir, bringing something back to heal or improve their community, now fully transformed.

When to Use This Structure

The Hero's Journey is perfect for epic fantasy (The Hobbit), grand-scale science fiction (The Matrix), and adventure stories (Finding Nemo) where the protagonist's internal transformation is just as important as their external quest. Use it when you want to create a story with deep mythological roots and a focus on personal growth, mentorship, and sacrifice. It excels at building immersive worlds and crafting a central figure whose journey inspires the audience.

3. Five-Act Structure (Freytag's Pyramid)

The five-act structure, often visualized as Freytag's Pyramid, is a classic dramatic framework that organizes a story into five distinct parts. Developed by Gustav Freytag to analyze Shakespearean and Greek tragedies, this model emphasizes a symmetrical rise and fall of tension around a central climax. It is one of the most foundational narrative structure examples for stories focused on a single, decisive turning point.

This structure provides a meticulous blueprint for mapping a story's dramatic arc. Its power lies in its rhythmic pacing, which builds suspense methodically before guiding the audience through the consequences of the story's peak conflict.

The pyramid shape visually represents the story's progression, with the climax forming the apex of the narrative arc.

How It Works: A Strategic Breakdown

Freytag's Pyramid breaks a narrative into five sequential acts, each serving a specific function in developing and resolving the central conflict.

- Act I: Exposition. This initial act introduces the characters, setting, and the established status quo. It lays the groundwork for the conflict and includes the inciting incident that sets the story in motion. In Romeo and Juliet, this is the street brawl and the introduction of the feuding families.

- Act II: Rising Action. A series of complications and obstacles build tension and develop the conflict. The protagonist grapples with challenges that escalate the stakes. For example, this includes Romeo and Juliet's secret meeting and marriage.

- Act III: Climax. This is the turning point of the story, a moment of peak tension from which there is no return. The protagonist makes a critical decision or faces a major event that changes the story's trajectory forever. The duel where Romeo kills Tybalt serves as this irreversible climax.

- Act IV: Falling Action. This act deals with the direct consequences of the climax. Tension begins to decrease as the characters react to the turning point, and the conflict moves toward its inevitable conclusion.

- Act V: Denouement. The story's final resolution, or catastrophe in a tragedy, where conflicts are resolved and a new normal is established. Loose ends are tied up, and the narrative concludes.

When to Use This Structure

The five-act structure is exceptionally effective for tragedies, dramas, and literary fiction where the exploration of consequences is as important as the conflict itself. Works like The Great Gatsby and Hamlet use this framework to create profound thematic resonance. Use it when you want to place a heavy emphasis on the fallout from a single, pivotal moment, allowing for a deep exploration of character and theme in the aftermath. It is perfect for stories that aim for a more traditional, literary feel with a clear and deliberate pace.

4. In Medias Res

In medias res, Latin for "into the middle of things," is a narrative technique that thrusts the audience directly into a crucial moment of action or conflict. Instead of a linear beginning, the story starts at a high point of tension, immediately capturing attention and raising questions. The necessary backstory and context are then revealed gradually through flashbacks or dialogue, making it a powerful tool among narrative structure examples.

This approach creates instant engagement by prioritizing intrigue over exposition. By dropping the audience into a compelling situation, it generates immediate curiosity, forcing them to piece together the events that led to the opening scene. This active participation can create a deeper and more memorable viewing or reading experience.

The visualization above shows how the narrative begins at a central point of action, with the preceding events (the "beginning") and subsequent outcomes (the "end") filled in around it.

How It Works: A Strategic Breakdown

In medias res functions by reordering the traditional plot sequence to maximize initial impact. It hinges on a carefully chosen opening that encapsulates the story’s core themes or conflicts.

- The Hook: The story opens with a dramatic, confusing, or action-packed scene. The pilot of Breaking Bad is a masterclass in this, opening with Walter White in his underwear, driving an RV through the desert with two bodies in the back. The audience is immediately hooked and needs to know why.

- The Reveal: Following the intense opening, the narrative strategically reveals backstory. This can be done through flashbacks, character conversations, or other expository devices that fill in the gaps without halting the forward momentum.

- The Convergence: The narrative eventually catches up to the opening scene, providing full context and raising the stakes. At this point, the audience understands the "how" and "why," and the story proceeds toward its climax and resolution from a new, informed perspective.

When to Use This Structure

This structure is exceptionally effective for thrillers, action films, and crime dramas where mystery and suspense are paramount. Use it when you want to bypass a slow setup and immediately establish a tone of urgency or disorientation. It works well for stories like Pulp Fiction or The Odyssey, where the non-linear journey of discovery is as important as the destination itself. It is a fantastic choice for grabbing an audience from the very first page or frame, but it requires careful planning to ensure the eventual reveals are satisfying and not confusing.

5. Circular/Cyclical Narrative

The circular or cyclical narrative is a structure that artfully begins and ends in the same place, either literally or thematically. This framework creates a powerful sense of unity and inevitability, suggesting that some journeys are destined to return to their origins. As one of the more philosophical narrative structure examples, it excels at exploring themes of fate, history repeating itself, and personal growth.

This structure’s appeal lies in its satisfying sense of closure. The ending doesn't just repeat the beginning; it re-contextualizes it, revealing deeper meaning. The protagonist’s journey, though it ends where it started, has fundamentally changed them, allowing the audience to see the familiar starting point through a new lens.

How It Works: A Strategic Breakdown

A circular narrative is built on the foundation of repetition and transformation. The ending mirrors the opening, but the character’s internal state or understanding has evolved.

- The Starting Point: The story opens by establishing a specific scene, theme, or character state. This initial setup is crucial as it becomes the anchor to which the narrative will eventually return. In The Lion King, this is the presentation of Simba at Pride Rock, establishing the "Circle of Life."

- The Journey Outward: The character embarks on a journey that takes them far from their starting point, much like a traditional linear plot. They face conflicts and undergo significant change.

- The Inevitable Return: The story concludes by returning to the initial setting or a mirrored scenario. However, the protagonist is now changed. In The Lion King, the story ends with Simba presenting his own cub, completing the circle but now as a wise king, not an innocent prince. The return feels earned and meaningful.

This structure emphasizes that even when we return to the same circumstances, we are not the same person. The cycle is completed, but the character has broken their own internal loop of immaturity or ignorance.

When to Use This Structure

The circular narrative is perfect for stories centered on inescapable destinies, memory, or the cyclical nature of life and history. It is highly effective in dramas (The Great Gatsby), philosophical comedies (Groundhog Day), and mind-bending science fiction (Arrival). Use this structure when you want the ending to echo the beginning in a profound way, prompting the audience to reflect on the entire journey. It is ideal for writers looking to create a story that feels both complete and thematically resonant, leaving a lasting, reflective impression.

6. Multiple Timeline/Non-Linear Structure

The multiple timeline or non-linear structure shatters chronological order, presenting story events in a fragmented sequence. By using techniques like flashbacks, flash-forwards, or parallel plotlines separated by time, this framework manipulates the flow of information to build mystery, create thematic resonance, and mirror the complex nature of memory. It is one of the more experimental narrative structure examples for challenging audience perceptions.

This structure’s power lies in its ability to recontextualize events. A scene’s meaning can transform entirely based on what the audience learns from a different timeline, turning the viewing experience into an active puzzle that demands engagement.

How It Works: A Strategic Breakdown

A non-linear narrative relies on anchor points and thematic links to guide the audience through its fractured timeline. Its success depends on carefully controlled revelations.

- Fragmented Sequence: Events are deliberately presented out of order. For example, a story might start with the aftermath of a major event and use flashbacks to slowly reveal what led to it, as seen in Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction.

- Parallel Timelines: The narrative simultaneously follows two or more distinct timelines. These timelines might feature the same character at different ages or different characters whose stories eventually converge. Westworld masterfully uses this to hide major plot twists in plain sight.

- Thematic Juxtaposition: The primary goal is often to draw parallels between events, characters, or ideas across different time periods. In Cloud Atlas, stories separated by centuries are linked by a shared theme of human connection and rebellion against oppression.

Christopher Nolan’s Memento is a quintessential example, using two timelines: one moving forward (in black and white) and one moving backward (in color) to mimic the protagonist's anterograde amnesia.

The video above breaks down how non-linear storytelling creates an immersive experience by controlling what the audience knows and when.

When to Use This Structure

Use a non-linear structure when your story's theme is deeply connected to concepts like memory, fate, or the impact of the past on the present. It is perfect for psychological thrillers, mysteries, and complex character studies where the "why" and "how" are more important than the "what." This structure is ideal if you want to create a powerful sense of dramatic irony, as the audience can piece together information that the characters in one timeline do not yet possess.

7. Frame Narrative (Story within a Story)

The frame narrative is a sophisticated literary device where a primary story serves as a container for a secondary, embedded narrative. The outer "frame" story provides context, introduces a narrator, and sets the stage for the inner tale. This nesting technique adds layers of meaning, allowing the frame to comment on, question, or reinforce the themes of the story it contains, making it a uniquely versatile tool among narrative structure examples.

This structure's power lies in its ability to manipulate perspective and distance. By having a character narrate the main events, the author can introduce bias, create suspense, or explore the act of storytelling itself, turning a simple plot into a complex, multi-layered experience.

How It Works: A Strategic Breakdown

A frame narrative creates a "story within a story" dynamic, where the relationship between the two layers is as important as the plots themselves.

- The Frame Story (Outer Layer): This is the narrative that begins and often ends the work. It establishes the setting and characters for the telling of the inner story. A key element is the narrator of the frame, whose motivations for telling the tale are often central. For example, in Titanic, elderly Rose is the frame narrator, and her present-day search for the necklace provides the context for recounting her past.

- The Embedded Story (Inner Layer): This is the main narrative, the story being told by the frame’s narrator. It contains the core conflict, characters, and plot. In The Princess Bride, the grandfather reading the book is the frame, while the adventures of Westley and Buttercup form the embedded story. The grandfather’s interruptions (the frame) directly influence how the audience perceives the fantasy tale.

The interplay between these layers allows for commentary on memory, truth, and the power of stories.

When to Use This Structure

The frame narrative is exceptionally effective for stories that explore subjectivity, memory, or the nature of truth itself. It’s ideal for historical fiction (Titanic), epic collections of tales (One Thousand and One Nights), and psychological or philosophical explorations (Heart of Darkness). Use this structure when you want to create a specific tone or lens through which the audience experiences the main plot. It adds credibility, provides a platform for thematic commentary, and allows for a non-chronological delivery of information that can build mystery and depth.

Narrative Structure Comparison of 7 Examples

| Narrative Structure | Implementation Complexity 🔄 | Resource Requirements ⚡ | Expected Outcomes 📊 | Ideal Use Cases 💡 | Key Advantages ⭐ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Three-Act Structure | Moderate - clear, linear steps with pacing risks | Moderate - needs balanced pacing and planning | Clear narrative momentum with satisfying progression | Feature films, novels, TV episodes, marketing | Universally understood, adaptable, time-tested |

| Hero's Journey (Monomyth) | High - 17 stages with archetypal roles | High - involves rich character and thematic development | Deep emotional transformation and universal resonance | Epic quests, fantasy, mythological stories | Resonates with universal experiences, flexible |

| Five-Act Structure (Freytag) | Moderate to High - five distinct structural acts | Moderate - needs tension build and resolution control | Balanced tension and aftermath emphasis | Theatrical productions, tragic narratives | Detailed tension framework, classical effectiveness |

| In Medias Res | High - non-linear opening with flashbacks | High - requires skilled exposition handling | Immediate engagement and suspense | Action, thrillers, complex storytelling | Grabs attention quickly, creates curiosity |

| Circular/Cyclical Narrative | Moderate - planned repetition and foreshadowing | Moderate - requires thematic consistency | Sense of completion and thematic unity | Philosophical, metaphysical, redemption arcs | Strong thematic resonance, satisfying closure |

| Multiple Timeline/Non-Linear | Very High - complex timeline management | High - demands meticulous planning | Sophisticated narrative complexity and thematic depth | Psychological drama, mystery, sci-fi | Engages active audience, controls info flow |

| Frame Narrative (Story within a Story) | High - multiple nested perspectives | Moderate to High - needs layered storytelling | Thematic depth, multiple viewpoints | Literary fiction, historical, and complex tales | Adds credibility, thematic richness, multi-perspective |

From Structure to Story: Your Next Steps in Narrative Design

We have journeyed through a diverse landscape of narrative architecture, exploring seven distinct blueprints that have shaped countless memorable stories. From the classical symmetry of the Three-Act Structure to the intricate, memory-like web of a Non-Linear Narrative, it is clear that a story’s framework is far from a creative limitation. Instead, it is a powerful tool for shaping audience emotion, managing suspense, and delivering a resonant message.

The true takeaway is that structure is not a formula to be followed rigidly, but a scaffold to support and elevate your unique vision. The most compelling narrative structure examples reveal that masterful storytellers select their framework with intention, matching the architecture to the emotional core of the story they wish to tell.

Choosing Your Narrative Blueprint

The key to applying these concepts is to move from passive understanding to active experimentation. Your next step involves a critical self-assessment of your own storytelling goals. Consider the kind of experience you want to create for your audience.

- For a story of transformation and triumph: The Hero’s Journey provides a deeply satisfying and universally understood map for character growth.

- For a story that begins with a bang: Starting In Medias Res immediately hooks your audience by dropping them into the heart of the conflict, creating instant intrigue.

- For a complex, thematic exploration: A Frame Narrative or Multiple Timeline structure can add layers of meaning, allowing you to juxtapose ideas, time periods, and perspectives in a powerful way.

The ultimate goal is to build a narrative that feels inevitable and emotionally honest. The structure should become invisible to the audience, seamlessly guiding their experience without ever feeling mechanical or predictable.

From Theory to Practice: Building Immersive Worlds

Mastering these structures is especially vital for creators in interactive and dynamic mediums. When designing custom AI characters or roleplay scenarios, for instance, the narrative framework is what makes the experience feel alive and consequential. By embedding the principles of Freytag’s Pyramid or a Cyclical Narrative into a character’s backstory and potential conversation paths, you can create companions that offer more than just simple chat. You create a living story for the user to step into.

These frameworks provide the bones; your creativity provides the soul. Don't be afraid to mix and match elements. Perhaps your character’s journey follows a three-act arc, but you reveal their backstory through non-linear flashbacks. The possibilities are endless. The most important step is to begin. Choose a structure that resonates with your idea, start outlining, and build your world one plot point at a time. The most powerful stories are waiting for you to give them form.

Ready to apply these narrative principles to create truly dynamic and engaging characters? Explore Luvr AI to design custom AI companions with deep backstories and personalities, all built on the kind of powerful storytelling frameworks we've discussed. Bring your ideal characters to life and start crafting your own immersive narrative experiences today at Luvr AI.